In the first decade of the 20th century, Henry Street Settlement hosts arts classes in the dining room at the Settlement’s headquarters and in the gym at 303 Henry Street. Students take dance, music, and ceramics lessons. These classes lay the groundwork for future arts education programs at the Abrons Arts Center.

Lillian Wald, the founder of Henry Street Settlement, believes that the arts are essential to well-being, and that all people, regardless of income, should have access to the arts.

Music class in the dining room at Henry Street’s headquarters, 1910. Henry Street Settlement Archives.

In the first decade of the 20th century, Henry Street Settlement hosts arts classes in the dining room at the Settlement’s headquarters and in the gym at 303 Henry Street. Students take dance, music, and ceramics lessons. These classes lay the groundwork for future arts education programs at the Abrons Arts Center.

Lillian Wald, the founder of Henry Street Settlement, believes that the arts are essential to well-being, and that all people, regardless of income, should have access to the arts.

Music class in the dining room at Henry Street’s headquarters, 1910. Henry Street Settlement Archives.

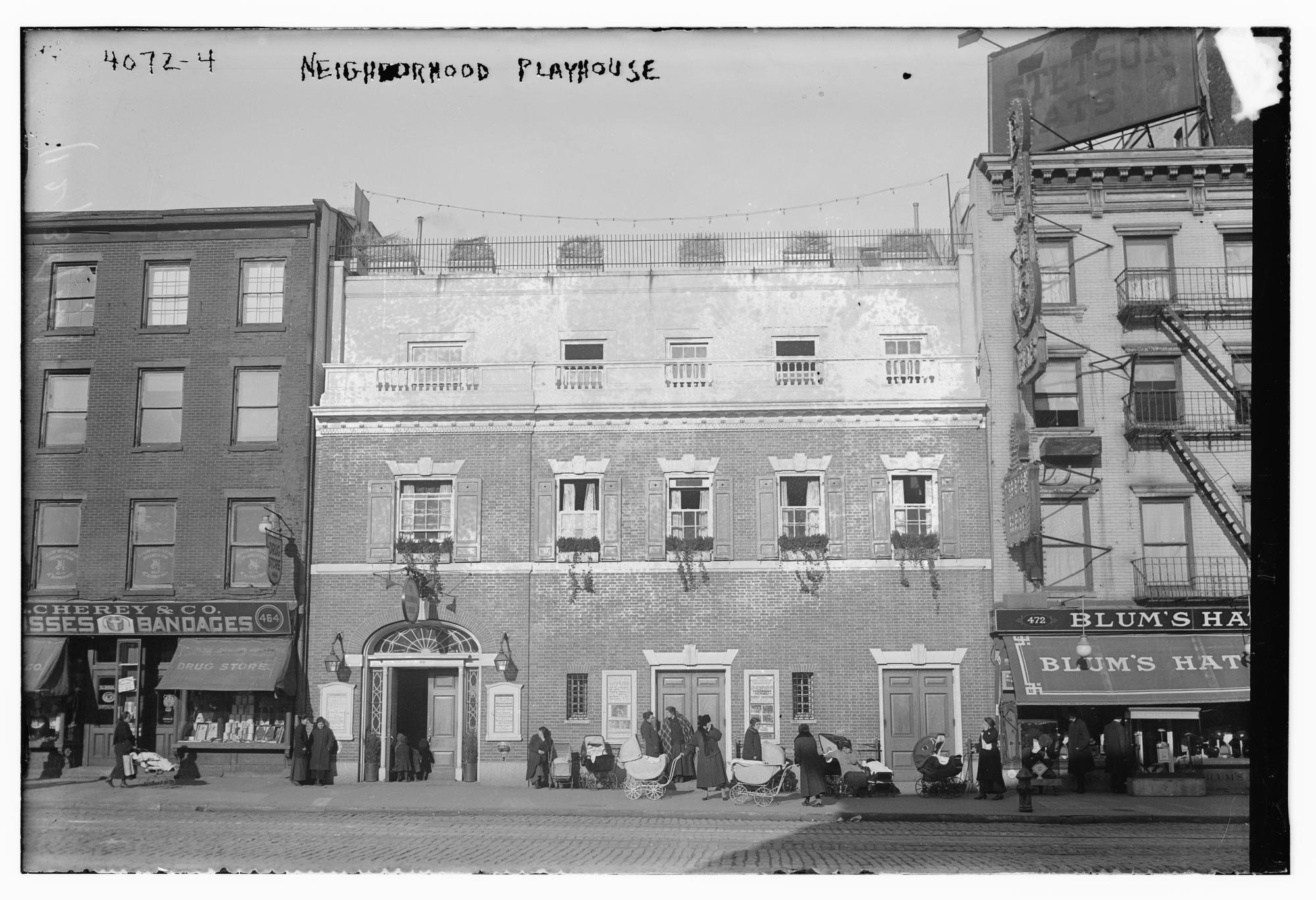

In 1915, philanthropist sisters Alice Lewisohn (1883–1972) and Irene Lewisohn (1892–1944) buy a lot on the corner of Grand and Pitt Streets in New York City’s Lower East Side and found the Neighborhood Playhouse Theater. The modest three-story red brick structure, designed by architects Harry C. Ingalls and F. Burrall Hoffman, Jr., features both motion pictures and theatrical performances.

Street-view of the Neighborhood Playhouse Theater, Library of Congress.

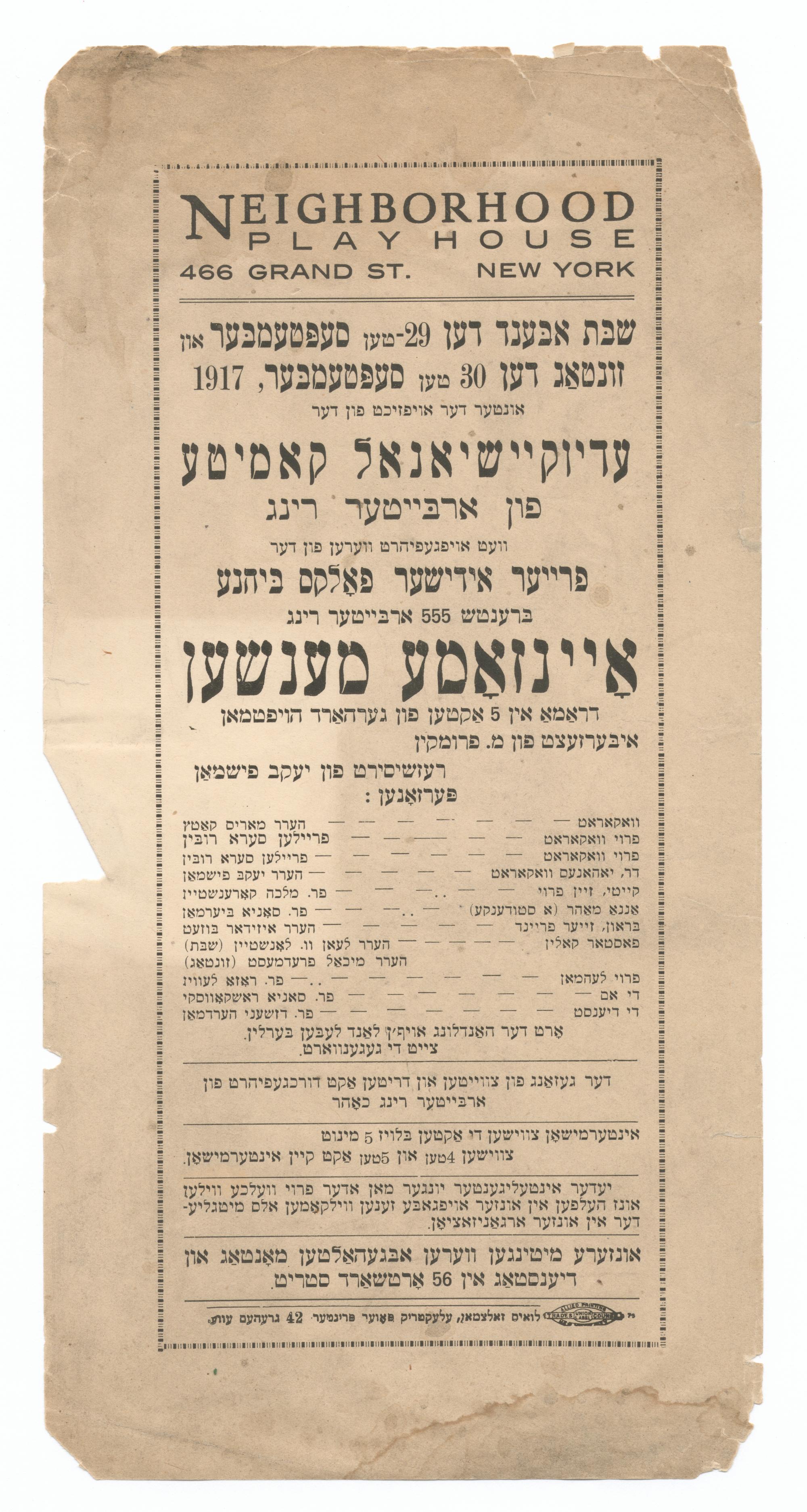

Many of the earliest productions at the Playhouse are in Yiddish, the language of the Settlement’s Jewish neighbors. While some settlements prioritize assimilation into American culture, Henry Street’s founder Lillian Wald believes immigrants' cultures and languages are to be celebrated. Taking a radical approach at the turn of the 20th century, Henry Street provides immigrants with resources and tools to succeed in their new home, but does not push assimilation as the ultimate goal.

Playbill from Aynzame Menshen, 1916. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

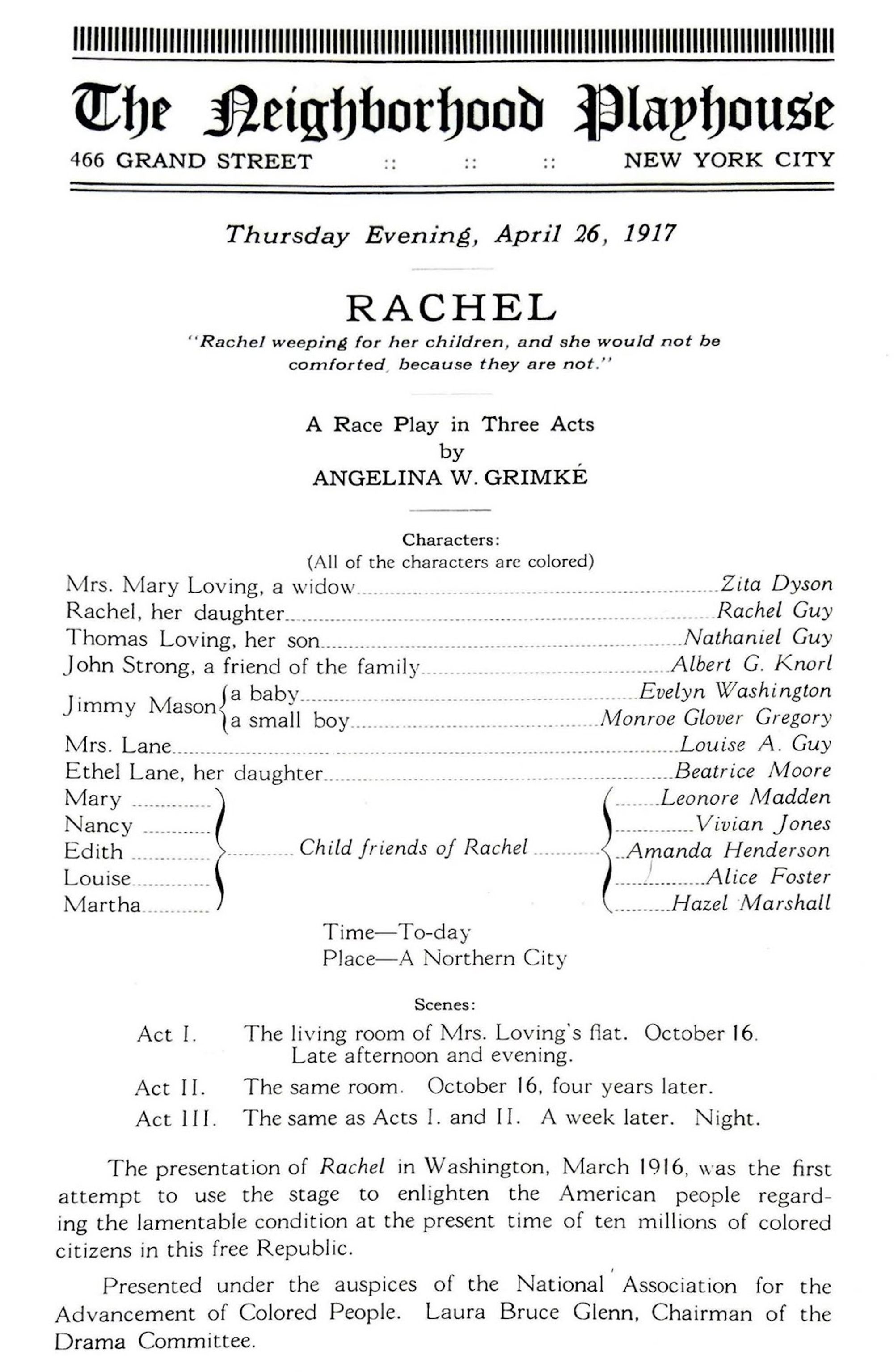

In 1917, Harlem Renaissance journalist, teacher, playwright, and poet Angelina Weld Grimké’s play “Rachel” is performed at the Neighborhood Playhouse. Originally funded by the NAACP and known as one of the first plays by a Black playwright with an all-Black cast performed for an integrated audience, “Rachel” primarily aims to educate white audiences about the truth of racial violence in America.

The NAACP, which had formed eight years earlier, is connected to Henry Street Settlement's work throughout that decade. In 1909, a reception preceding one of the earliest meetings of the NAACP's founding members takes place in the dining room at the Settlement headquarters. Attendees include W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells, and Jane Addams.

Rachel, 1917. Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre Collection.

By 1920, the Playhouse becomes renowned for its avant-garde productions, often incorporating dance, music, and poetry, and for its popular revue, The Grand Street Follies. This vibrant, daring satirical production opens in 1922 and returns annually through the end of the decade.

Many early 20th century modern dancers and artists find a professional home at the Neighborhood Playhouse, including Martha Graham and composers Ernest Bloch, Kurt Schindler, and Louis Horst. Other notables include Agnes de Mille, Laura Elliott, Doris Humphrey, and Charles Weidman. This experimental theater and two other off-Broadway “little theaters” (Providence Playhouse and Washington Square Players) form the foundation for modern American performance.

Billy Rose Theatre Division, NYPL. "Grand Street Follies", New York Public Library Digital Collection.

The Playhouse acting company officially disbands in 1927 and the building is renamed the Henry Street Playhouse. The Lewisohn sisters and Rita Wallach Morganthau go on to establish the Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre in 1928. Irene Lewisohn would also found the Museum of Costume Art in 1937, which would later merge with the Metropolitan Museum of Art and is now known famously as the Met Costume Institute.

The interior of the Neighborhood Playhouse Theater at 466 Grand Street. Henry Street Settlement archives

During the Great Depression, the arts take on new meaning at Henry Street Settlement. Throughout the 1930s, the Playhouse Theater stage becomes a place to articulate the many challenges faced by Lower East Siders. These performances, developed by the WPA Federal Theater Project and called “Living Newspapers,” dramatize everyday issues such as rising milk prices, hunger, housing, and unemployment.

A scene from “Dollars and Sense”, one of the Living Newspapers presented at Henry Street, 1930’s. Henry Street Settlement Collection.

During the 1940s, Henry Street’s music school expands. In 1946, famed folk singer Jean Ritchie works at the Settlement teaching music to 8- to 10-year-olds. Ritchie, who is fresh out of college and new to New York City, is at the very beginning of her musical career. She will go on to become one of the most influential folk musicians of our time.

Jean teaches a game at the Henry Street Settlement. George Pickow and Jean Ritchie Collection

In 1948, Alwin Nikolais is appointed director of the Henry Street Playhouse, where he forms the Playhouse Dance Company, later renamed and known as the Nikolais Dance Theatre. At Henry Street, Nikolais begins to develop his own world of abstract dance theater, portraying humans as part of a total environment. Nikolais redefines dance as “the art of motion which, left on its own merits, becomes the message as well as the medium.” Mr. Nikolais is joined by Murray Louis, who becomes a driving force in the Playhouse Company, Nikolais’s leading dancer, and longtime collaborator.

Nikolais & Murray Louis Dance. Henry Street Settlement Archives

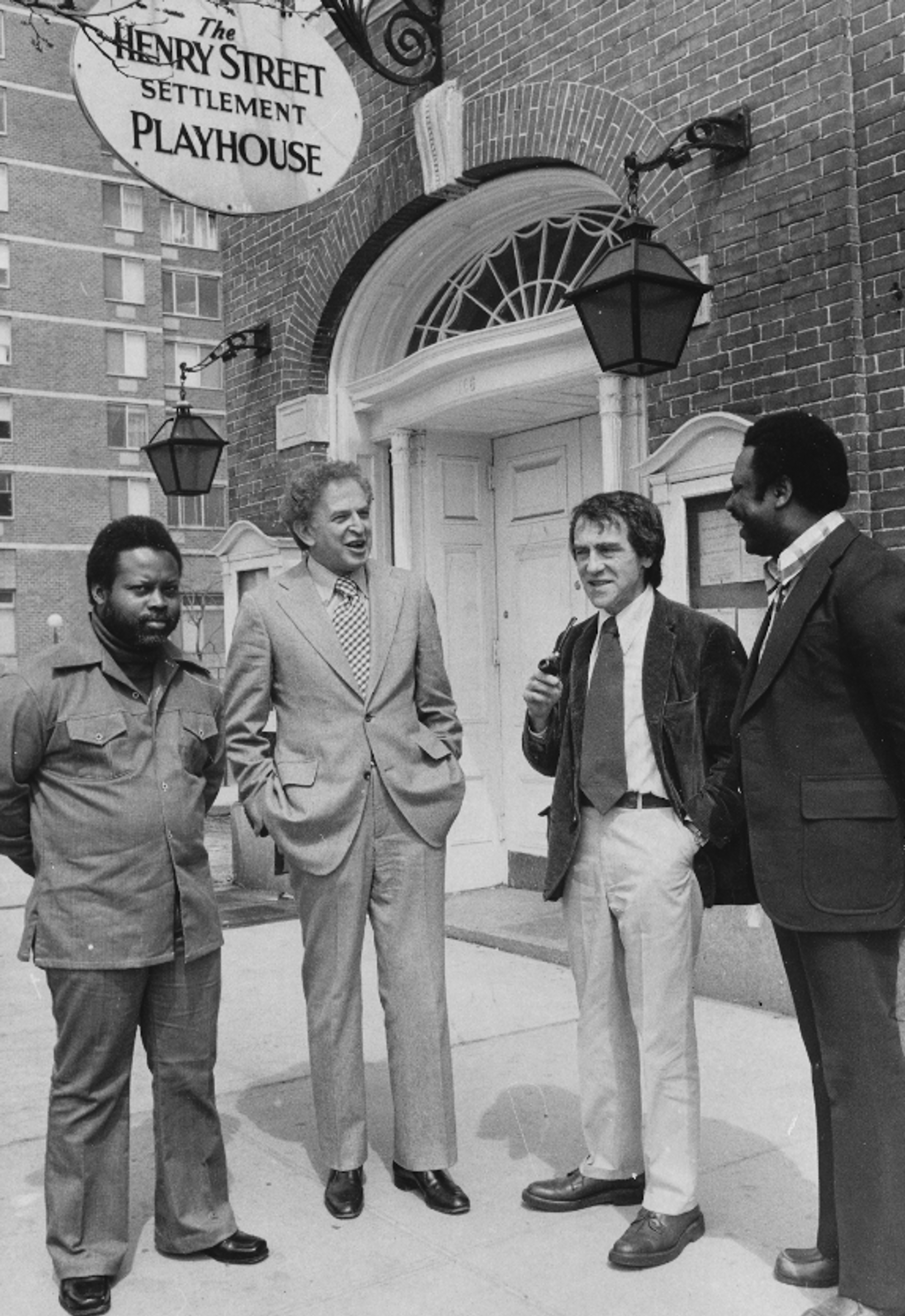

In 1970, Woodie King Jr. founds the New Federal Theatre, initially funded by Henry Street and a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts. The theater, whose name hearkened to the Great Depression’s Federal Theatre, pushes to integrate people of color into mainstream theater.

Most of the plays King mounts at the theater are by Black playwrights. As King recalls, “Many white-controlled theatres produce only European plays that are directed to their own need to glorify the past,” while “African Americans are not integral to their past in any kind of positive way. That [leaves] me with a large canvas of untold stories.”

Young people in and around Henry Street often work on productions, building sets, sewing costumes, and working on the lighting crew. For this reason, King calls the New Federal Theatre a “professional theater involving community.”

In 1975, the Arts For Living Center is built as an extension to the Neighborhood Playhouse Theater. Architect Lo-Yi Chan of the firm Prentice & Chan, Ohlhausen develops the new building’s design in collaboration with an intergenerational cohort of local residents.

A new kind of urban arts center is born, one that serves a wide array of needs and interests of local and visiting communities. Abrons is widely regarded as a case study for the role that architecture can play in facilitating access to the arts for a diverse public.

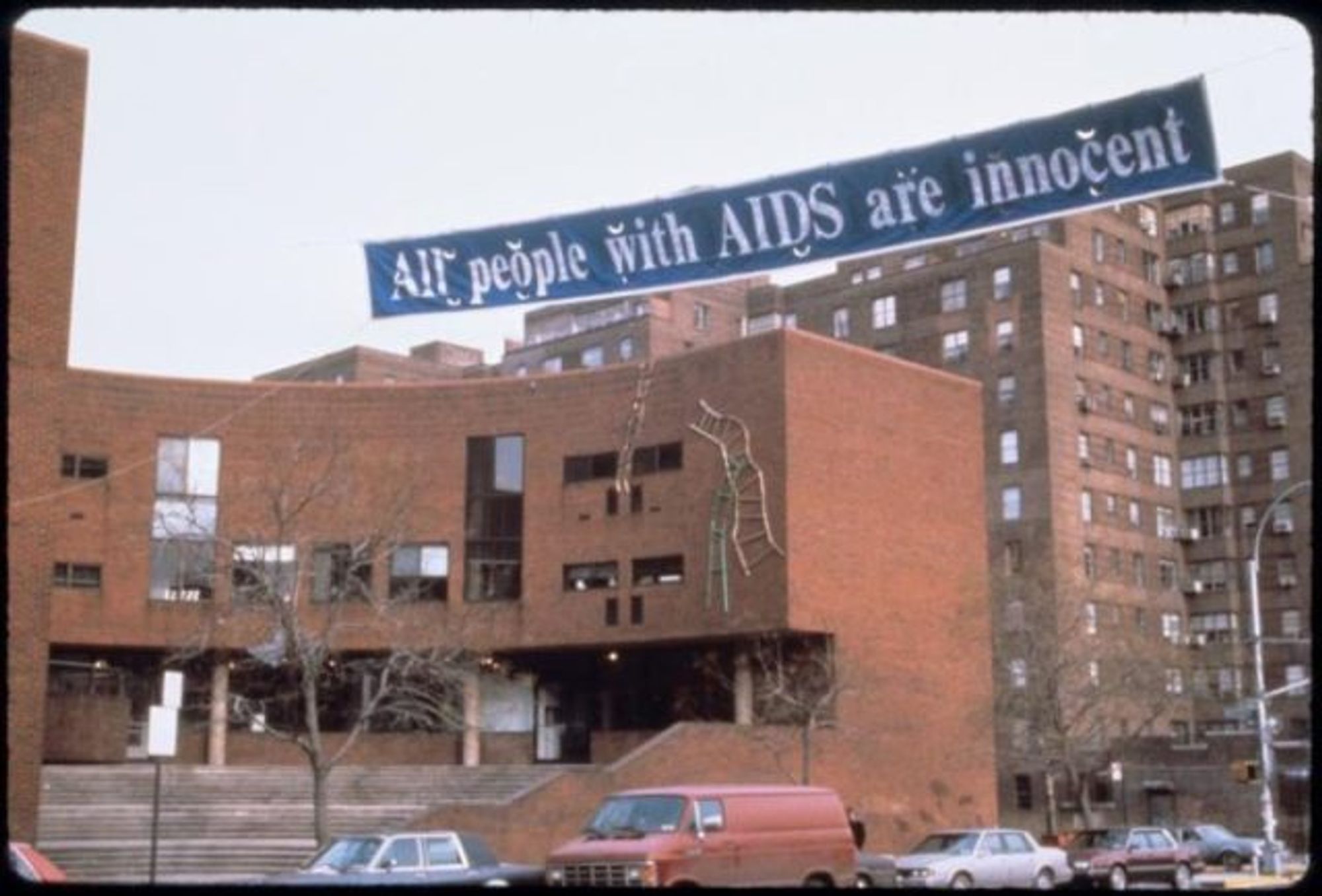

As part of the 1989 exhibition “Images and Words: Artists Respond to AIDS,” the art collective Gran Fury hangs a 30-foot banner reading “All People with AIDS are Innocent” across Grand Street right outside the Abrons Arts Center.

This banner is one of many public works of protest and provocation created by Gran Fury in response to the ongoing AIDS epidemic. Known as ACT UP’s “unofficial propaganda ministry,” this collective is responsible for much of the stunning work we associate with AIDS activism today, including the SILENCE = DEATH graphic.

The Lower East Side is hit particularly hard by the AIDS epidemic. In the early 1980s, Henry Street Settlement's Community Consultation Center is designated one of the first official mental health providers for families affected by AIDS.

“Banner in front of Henry Street Settlement”, 1989. NYPL Digital Collections.

Abrons Arts Center’s education programming flourishes throughout the 1990s, with classes in visual art, dance, music, and theater. Urban Youth Theater is founded, providing teens the opportunity to explore the world of performance.

Henry Street Settlement Archives, 1990-2000.

Henry Street Settlement restors both the interior and exterior of the Playhouse Theater.

Image by Whitney Browne

As the Covid-19 pandemic shutters arts venues nationwide, many Abrons Arts Center team members and artists are redeployed into both staff and volunteer roles to meet the community’s urgent need for food home delivery. As Henry Street’s pantries expand, the Abrons Arts Center’s main stage becomes the central coordinating site for food distribution. Many Abrons arts educators and performers adapt their work to online formats.

Photograph by Michael Loccisano, Getty Images